Barbiturates are a class of drugs were popular for the first half of the 20th century as sedatives and anesthetics. However, their severe risks of addiction and overdose, highlighted in high-profile cases such as Marilyn Monroe’s death from Nembutal (pentobarbital) in the 1960s, quelled its popularity as an easily accessible sleeping pill. Today, most countries treat barbiturates as controlled substances, with minimal medical use.

A Short History of Barbiturates

Adolf von Baeyer: The Chemist Who Started it All

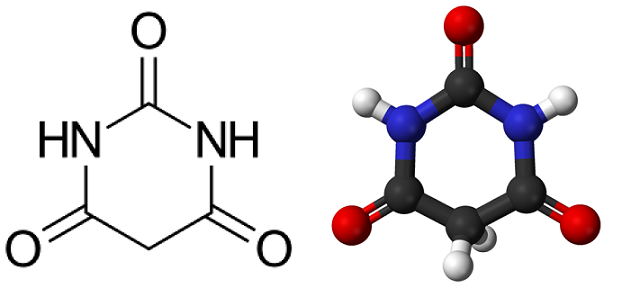

Way back in 1864, the prolific synthetic chemist Adolf von Baeyer was in his lab working on a new molecule he had recently created. It was a reasonably simple-looking organic compound with a heterocyclic structure, which Baeyer named barbituric acid (apparently because, at the time, he was infatuated with a lady called Barbara).

Baeyer—who later in 1905 won the Nobel prize for his work on organic dyes—was constantly dreaming up and synthesizing new compounds. Hence, he could be forgiven for not realizing the medical significance of barbituric acid at the time. Just as Adolf von Baeyer is now recognized as a founding father of organic chemistry, barbituric acid would be known as the precursor to an important family of compounds known as barbiturates.

Commercialization of Barbital (Diethylbarbituric Acid)

However, barbituric acid has no therapeutic activity in the human body. This is because the molecule is too polar and cannot be absorbed easily, leading to poor bioavailability. It was Baeyer’s brilliant student Emil Fischer—who actually won a Nobel prize in 1902, 3 years before Baeyer did—who cracked the barbiturate code.

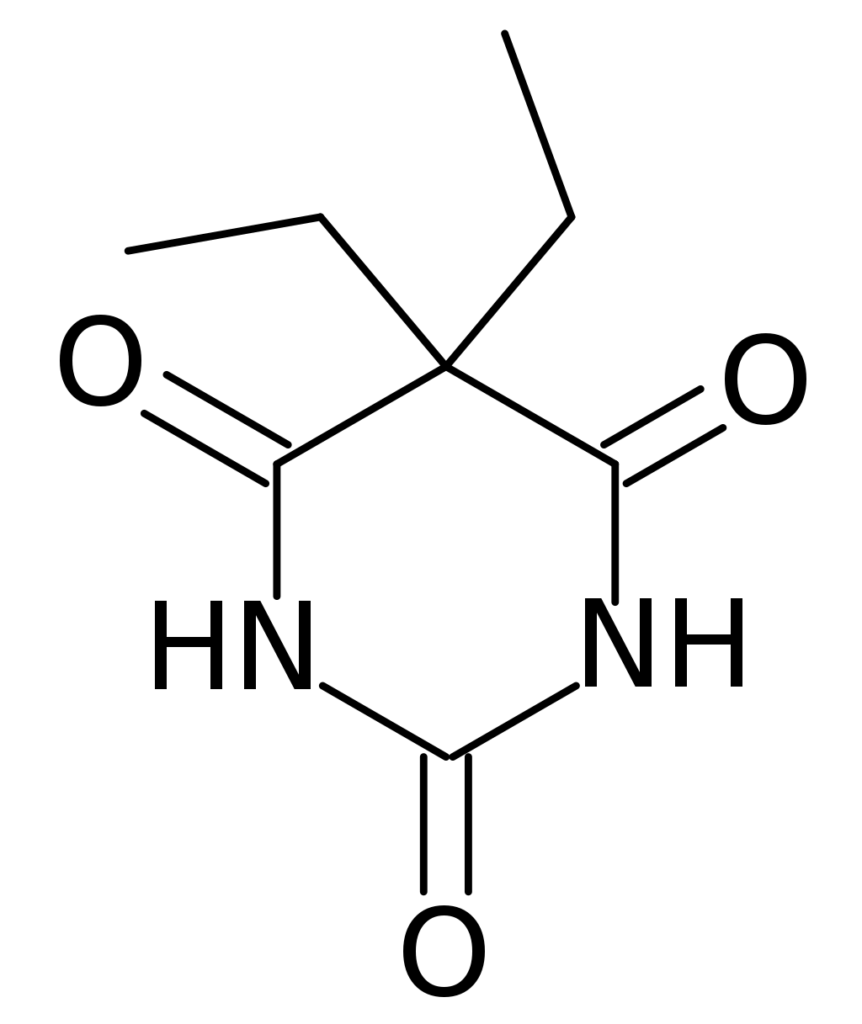

Without modern medicinal chemistry to aid his efforts, Fischer figured out that attaching hydrophobic ethyl groups to barbituric acid gave the new chemical hypnotic and sedative properties.

This molecule (diethylbarbituric acid) was branded and sold as Veronal in Germany and Barbital in the U.S. This was a time when regulatory agencies like the FDA didn’t exist, and medicines could be exported and sold pretty much freely.

Barbiturates for the Masses

The success of Veronal/Barbital led to an explosion of new barbiturates in the early 20th century. Over 2,500 derivatives of barbiturate acid were synthesized, with varying degrees of therapeutic success. They were prescribed for treating conditions like insomnia, anxiety and seizures and used as anesthetics during surgery.

Several notable examples of barbiturate drugs include:

- Phenobarbital: After realizing the effectiveness of diethylbarbituric acid, Emil Fischer promptly synthesized the more potent phenobarbital several years later. It was sold under the brand name Luminal by pharmaceutical company Bayer and remained popular as a sedative until the 1960s.

- Secobarbital: A barbiturate synthesized by Swiss chemist Ernst Preiswerk in 1934, it was sold in the U.S. by Eli Lilly as Seconal for the treatment of epilepsy, insomnia as well as an anesthetic for certain medical procedures.

- Amobarbital (Amytal): A short-acting barbiturate, first synthesized in 1923 and sold by Eli Lilly. Although it was approved for anxiety, epilepsy and insomnia, it was commonly misused off-label due to its fast-acting inhibitory properties.

- Pentobarbital: Another short-acting barbiturate sold as Nembutal in the 1930s, this drug was actually used in a lethal injection for an execution carried out in Oklahoma in 2010. It is no longer commercially available.

- Sodium Thiopental (Trapanal): This rapid-acting barbiturate was developed by Abbott Laboratories in the 1930s. Because of its quick onset of action (as little as 30 seconds), it is used to induce unconsciousness in situations such as a cesarean section delivery.

- Methohexital (Brevital/Brietal): Another rapid-acting barbiturate with similar properties to sodium thiopental, this drug was also used as a general anesthetic. It was developed by Schering AG (present-day Merck & Co.) in the 1950s.

Barbiturates enjoyed immense popularity in the 1950s and 1960s as easily accessible, quick-acting anxiety relievers or sleeping pills. At the peak of its popularity, 4 billion tablets were produced per year in the U.S. alone (enough to put 10 million adults to sleep every night). Some of the longer-lasting barbiturates were also used recreationally as hypnotic drugs under common names like “downers” or “barbs”.

Widespread Decline and Discontinuation

However, as the side effects and addiction potential of barbiturates became more widely known, their use began to decline. High-profile fatal overdoses like that of Marilyn Monroe in 1962 (her autopsy report found that she ingested 47 tablets of Nembutal) prompted the pharmaceutical industry to develop safer alternatives.

Benzodiazepines like diazepam (Valium) replaced the short-acting barbiturates as the primary treatment for anxiety and insomnia, while inhaled halogenated alkanes are the preferred method of general anesthesia today. These alternatives offer similar benefits to barbiturates but with a reduced risk of addiction and overdose.

Barbiturates are still used in certain medical situations today. For example, sodium thiopental and methohexital are used in anesthesia and euthanasia protocols. Phenobarbital is also an anticonvulsant for patients responding poorly to other seizure medications. However, no new barbiturate drug has been developed since the 1960s.

What Makes Barbiturates Such Risky Medication?

Poor Pharmacological Profile

Barbiturates are risky medicines because their effective dose is very close to their toxic dose. This means that people who experience their therapeutic benefits can be just a few tablets away from experiencing adverse reactions, such as reduced hallucinations, suppressed breathing and even coma and death.

In pharmacological terms, barbiturates have a narrow therapeutic window, which we now know makes for a lousy drug candidate. Barbiturates are also highly addictive, and tolerance builds up quickly in regular users. To top it all off, combining them with other drugs like alcohol enhances their effects.

Potent GABA Enhancers

Barbiturate drugs enhance the effects of the chemical gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the brain. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter, which is just a fancy way of saying it reduces brain activity when bound to specific proteins in the brain called GABA receptors.

GABA binding to the GABA receptor activates it, which causes “inhibitory” effects like muscle relaxation, reduced anxiety and sleepiness. When barbiturates enter the brain, they attach to GABA receptors in a way that enhances the effect of GABA, promoting these effects. Certain barbiturates can also affect other receptors in the brain, resulting in their anesthetic properties.

Barbiturates are potent drugs, which means only a tiny amount is needed to induce their effects. Comparing the relative potencies of the ones listed above by their ED50 (the dose required to produce effects in 50% of the population) values:

| Barbiturate Drug | Potency (ED50) |

|---|---|

| Phenobarbital (Luminal) | 540 mg |

| Secobarbital (Seconal) | No data |

| Amobarbital (Amytal) | No data |

| Pentobarbital (Nembutal) | 720 mg |

| Sodium thiopental (Trapanal) | 160 mg |

| Methohexital (Brevital) | 60 mg |

Featured Image: Bottle for ‘Veronal’ crystals, Germany, 1903-1950. Science Museum, London. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

About the Author

Sean is a consultant for clients in the pharmaceutical industry and is an associate lecturer at La Trobe University, where unfortunate undergrads are subject to his ramblings on chemistry and pharmacology.