Syringe needles resemble rapiers: they’re long, pointy and very good for stabbing. Hence, we should take extra care using syringes in the lab–we don’t want to pierce our skin and risk getting dosed with whatever chemical is inside! This guide shares the best practices for handling syringes in the lab, as shared by other scientists.

Syringes are helpful tools in the laboratory, often combined with a needle to extract and deliver air-sensitive or moisture-sensitive reagents. However, they can also present a hazard to the user. Here’s a quick breakdown of safety tips for using syringes and needles in the lab:

- Don’t use needles unless necessary

- Avoid re-capping needles

- Sharps bins (with needle grooves) are your friend

- Always be aware of where your free hand is

- Luer-lock syringes prevent needles from flying

- Check chemical compatibility of all components

- Store reusable syringes properly

- Seek medical attention quickly if poked!

Syringes in the Laboratory?

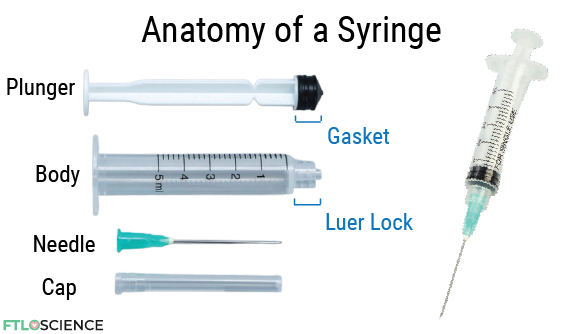

Anatomy of a Syringe

In case you haven’t seen a syringe in your life, or if you’ve forgotten how they look like, here’s a picture. Each component has a label, so you know the specific parts that we mention in this article.

Don’t Use Needles Unless Necessary

First off, you won’t need to read the rest of this article if you don’t have needles in your lab!

While syringes are useful, needles will not be necessary in every lab. You should only use them if your laboratory deals with air and moisture-sensitive reactions, where you need to pierce rubber septa to draw or deliver liquids.

Granted, such reactions are common in synthetic chemistry laboratories. But if you’re just using a syringe plus needle combo to reach the bottom of a reagent bottle, you’re doing it wrong!

Some moisture-sensitive high-purity chemicals, such as anhydrous ethanol, come with SureSeal caps. These bottle caps have a rubber septum built-in, so we need to use a syringe and needle combo to extract the chemical inside.

If you have no choice but to use syringe with needles in your laboratory, read on for our guide on safe practices.

Safe Handling of Syringes in the Lab

Re-capping Disposable Needles

To begin, disposable syringes and needles are just that, disposable. So you should have no need to reuse them, let alone re-cap them! Just throw the entire apparatus into the sharps bin when you’re done.

If you must reuse the syringe and needle; if the needle isn’t disposable, or perhaps for austerity measures, you can re-cap it this way:

- Place the needle cap flat on the table, with the opening facing toward you

- Pointing the syringe away from you, wriggle the needle into the cap with one hand

- Once housed safely, you can push down from the sides of the cap to tighten

- To remove the cap, hold the syringe body and use your thumb to pop the cap off

- The pointy end of the needle should never face you or any part of your body!

How to Dispose of Needles (But Not the Syringe)

If you only want to dispose of the needle, but not the syringe that it is attached to, the safest method is to use the catch in well-designed sharps bins. Simply insert the plastic portion of the needle into the grooves and pull up (or twist if it is it screwed on).

On the occasion that the needle is inserted too firmly onto the tip of the syringe, you can re-cap the needle (instructions above) and use a pair of pliers to gently twist the needle out. Remember to grip the plastic portion and not the metal tip of the needle.

Other Safety Tips for Accident-Prone Scientists

Your Free Hand is the One in Danger

Just like a magician’s misdirection turns your focus away from the action, the hand that holds the syringe is also the least likely to get injured (unless you’re a finger contortionist).

When inserting the needle into the rubber septum, keep your free hand (and face, of course) as far away as possible. It’s good practice not to hold on to the container you’re inserting a sharp needle into. A lapse in concentration or a little bump from behind, and you could end up accidentally poking yourself.

Use a clamp to hold the reagent bottle or flask while inserting the syringe. Even tiny vials have holders that can stop them from slipping away, so you don’t need to hold on to them like you see doctors do in movies!

Use Luer Locking Syringes

Have you ever pushed down hard on a plunger, trying to get the liquid out of a syringe, only to have the needle and contents fly across the fume hood? It turns out that’s the best way for a syringe with a needle attached to relieve pressure buildup.

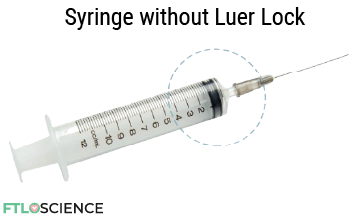

You can prevent this by using Luer locking syringes with threads at the tip (shown in our anatomy of a syringe image at the top of the article). Most needles are compatible with both Luer and non-Luer locking syringes.

They’re a little more expensive than typical syringes, but it’s well worth investing in safety, especially if your lab uses them for viscous liquids (you can refer to GHS labels to assess the risk of skin contact).

Check Chemical Compatibility of All Components

Certain chemicals react with the rubber gaskets on plungers, releasing gas. This pressure buildup can sometimes send the plunger flying out! It’s essential to figure out if whatever you’re drawing up into your syringe will react with rubber gaskets and purchase those with gasket-less plungers.

Although rubber gaskets seem to cause the most issues, it’s a good idea to review the compatibility of any new chemicals with all components of a syringe. For example, some solvents will melt the polypropylene body of the syringe, while very corrosive acids can dissolve metal needles.

There are syringes made from borosilicate glass that are compatible with most chemicals, though they are expensive. On the flip side, you can likely use them for years without losing their accuracy and durability.

Don’t Leave Syringes Lying Around the Lab

It’s easy to make a habit of leaving syringes and needles in the fume hood or on the lab bench while you tend to other tasks. Obviously, this isn’t a good idea! Keep yourself and other lab members safe by storing reusable syringes inside dedicated containers, which also helps prevent chemical contamination.

We get it, you have to step away in a hurry sometimes; when your reaction is time-sensitive, for example. In those cases, find temporary storage for your syringe, just so someone who accidentally sweeps their hand over your workspace won’t find themselves stabbed. It can be as simple as putting it needle-side down in a beaker or conical flask, or sticking the sharp end into a piece of foam.

If you (or others) have trouble keeping your workspace free of clutter, you can try applying 5S principles to your lab. This will help cultivate the habit of having a clean workspace, improving the lab’s safety and productivity.

Seek Medical Help ASAP if Poked!

If your skin gets pierced by a syringe containing a hazardous chemical, seek medical help immediately! This also applies if you’re unsure what was inside the syringe before the accident. The only exception would be if the syringe and needle were just taken out of their sterile packaging.

Some chemicals can have nasty effects if they get under the skin. Below are pictures of a finger stabbed with a needle containing a tiny amount of dichloromethane—a common organic solvent. Luckily, the scientist below had a skin graft within 2 hours, or they might have lost a finger.

Safety first !!!

— Sebastien Vidal (@SebVidalChem) February 20, 2019

So here is a simple question tweeps.

Which solvent could have caused such injury after poking one’s finger with a syringe and injecting 1-2 drops of solvent. 15 minutes and 2 hrs pictures pic.twitter.com/vCyaovYcyu

We hope you’ve learned a thing or two about the safe handling of syringes in the lab. We’d have done our job if this helped prevent someone from getting poked by a chemical-filled syringe. You’re now ready to learn how to draw and deliver liquids without being a danger to yourself and others!

About the Author

Sean is a consultant for clients in the pharmaceutical industry and is an associate lecturer at La Trobe University, where unfortunate undergrads are subject to his ramblings on chemistry and pharmacology.