Modafinil (Provigil) first entered the U.S. markets in 1998 after FDA approval. Although it was initially intended to treat narcolepsy and related sleep disorders, it quickly garnered a reputation as an off-label ‘smart drug’. We evaluate the effectiveness of modafinil as a smart drug using over two decades of scientific data in this article, looking at its effects on cognition and creativity, and the future of cognitive enhancers.

Modafinil, from Narcolepsy to Smart Drug

Modafinil was discovered in the 1970s by French neurophysiologist Michel Jouvet, then working for Lafon Laboratories. Like caffeine and methamphetamine, modafinil belongs to a class of drugs known as stimulants. In 1998, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use as a wakefulness-promoting agent for treating narcolepsy, under the brand name Provigil.

Modafinil’s mechanism of action is not well understood despite its effectiveness in treating narcolepsy, a condition in which the individual experiences excessive daytime sleepiness. There is evidence that it works by increasing dopamine in the brain, albeit through a different pathway than other stimulants1. However, the drug has found widespread use among non-narcoleptic individuals who use it to boost their productivity at work.

Modafinil has a half-life of around 11-14 hours, with the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes primarily responsible for its inactivation and excretion2. Unlike amphetamines, modafinil doesn’t appear to promote reinforcing behavior and hence has a low potential for addiction and abuse.

20 Years of Smart Drug Data

Cognitive enhancers or smart drugs fall into the category of nootropics, substances that may improve memory, creativity or motivation in individuals. Many supplements claim to have nootropic properties as U.S. law does not restrict such marketing, although few have been adequately evaluated. After its introduction into the market in 1998, modafinil quickly gained a reputation as an off-label nootropic, prompting independent studies into its effectiveness that continue to this day.

Early Clinical Trials

From a medical and scientific standpoint, it made sense for modafinil to be evaluated as a nootropic as it was already an approved drug. Phase IV (post-approval) trials could be conducted to see if the drug was used for other therapeutic targets, in what is known as drug repositioning. In this case, researchers would dose healthy individuals with modafinil and perform behavioral and cognitive studies to study its usefulness in these areas.

Despite 20 years of being on the market, it is important to note that relatively few human studies directly evaluate modafinil as a smart drug. Furthermore, sample sizes used in these studies are generally small and may not accurately reflect the population. This lack of studies is mainly due to regulatory issues, which we will discuss later in the article.

The first report of modafinil providing benefits to cognition is from a paper published in 2003. The participants who took the drug fared better in short-term memory tasks but exhibited significant delays in completing others3.

However, another study also published in 2003 found no changes in cognitive performance across a range of standardized tests4. Another double-blind crossover study in 2004 also found no significant effect of modafinil on the outcome of other cognitive tests5.

Modafinil in Low and High IQ Individuals

In 2005, a study was conducted by the research group that previously reported no effects, this time using a much larger sample size (n = 89)6. Again, no significant cognitive improvement was detected despite better statistical power, lending more credibility to the claim. Interestingly, the study showed evidence that modafinil might have a more significant effect on individuals with low to average IQ. In higher-performing individuals, modafinil did not offer cognitive benefits.

Several other studies performed later also showed that modafinil worked better in low baseline individuals. One study published in 2010 went further to show that while the drug led to greater improvement in low-performing participants, it was detrimental to higher-performing participants in visual processing speed and short-term memory tests7.

Additional Cognitive Effects

In many of these studies, participants were also assessed on their creativity. There is a consensus that problem-solving or ‘convergent’ creativity is not affected by modafinil. However, some studies report that the drug impairs ‘divergent’ creativity—the sort of creativity in which multiple associations are generated from a given subject8.

Although modafinil may not be the go-to smart drug to take before problem-solving or brainstorming tasks, it may benefit other cognitive abilities. Specifically, attentional tasks that some individuals might consider lengthy or boring may be easier to overcome under the effects of modafinil. Further clinical trials might shed more light on this and may even uncover additional cognitive effects.

A 2017 double-blind crossover study pitted chess players under the effects of modafinil against a computer program9. It was found that players on modafinil lost an abnormally large number of games due to running out of time. Removing these timed games from consideration showed marked improvement in the scores compared to placebo, suggesting that modafinil may improve performance in complex cognitive tasks but only in the absence of time pressures.

The Nootropics Landscape

Popularity of Modafinil as a Smart Drug

From the evidence collected over the past 20 years, there are definitely positive effects of using modafinil as a smart drug, especially in improving the attention span and memory of individuals with cognitive deficiencies. In students or adults working in a fast-paced environment, however, taking modafinil has not been shown to improve general performance.

Even so, the drug appeals to healthy individuals who take the drug for its mood-enhancing or wakefulness-inducing properties. A 2014 survey suggested that 1 in 5 students in UK universities have used modafinil. Its minor side effects coupled with a low risk of addiction make it reasonably safe, at least from short to medium-term use. Despite its popularity, modafinil is unlikely to be granted regulatory approval as a cognitive enhancer anytime soon.

Regulatory Issues and Implications

For a drug to be approved for a particular use, it must be deemed safe and effective. While the consensus is that modafinil provides a positive influence on mood and wakefulness, clinical trials have yet to build a strong case for its cognitive enhancing capabilities. Furthermore, long-term safety endpoints have yet to be conducted—and without significant sources of funding, they likely never will.

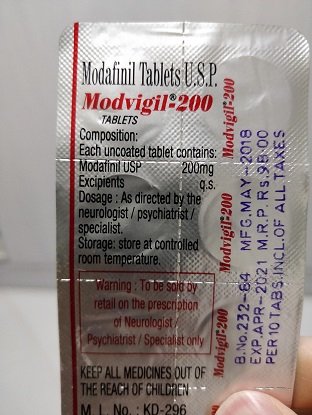

This lends a peculiar balance to the consumer landscape of modafinil. On one hand, manufacturers know that it would be futile to appeal to regulatory agencies to sell the drug as a cognitive enhancer. On the other, the demand for modafinil from the general public means that the illegal trade of the smart drug is likely to flourish.

As markets emerge to satisfy this demand, it becomes more difficult for authorities to control Modafinil’s use. Furthermore, the unregulated sale of the drug in this manner could increase the likelihood of counterfeits in the market, as manufacturers need not satisfy conventional regulatory requirements.

The dilemma facing regulatory agencies is approving a drug for use by individuals with no existing disease or impairment. How will its use be justified or controlled? If a true cognitive enhancing drug is indeed discovered one day, there will be no precedent. It is perhaps time for a wider discussion on the ethics of using such ‘smart drugs’ in everyday life.

Reference

- Ferraro, L., Tanganelli, S., O’Connor, W. T., Antonelli, T., Rambert, F., & Fuxe, K. (1996). The vigilance promoting drug modafinil increases dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens via the involvement of a local GABAergic mechanism. European journal of pharmacology, 306(1-3), 33-39.

- Ballas, C. A., Kim, D., Baldassano, C. F., & Hoeh, N. (2002). Modafinil: past, present and future. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 2(4), 449-457.

- Turner, D. C., Robbins, T. W., Clark, L., Aron, A. R., Dowson, J., & Sahakian, B. J. (2003). Cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology, 165(3), 260-269.

- Randall, D. C., Shneerson, J. M., Plaha, K. K., & File, S. E. (2003). Modafinil affects mood, but not cognitive function, in healthy young volunteers. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 18(3), 163-173.

- Liepert, J., Allstadt-Schmitz, J., & Weiller, C. (2004). Motor excitability and motor behaviour after modafinil ingestion–a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over trial. Journal of neural transmission, 111(6), 703-711.

- Randall, D. C., Shneerson, J. M., & File, S. E. (2005). Cognitive effects of modafinil in student volunteers may depend on IQ. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 82(1), 133-139.

- Finke, K., Dodds, C. M., Bublak, P., Regenthal, R., Baumann, F., Manly, T., & Müller, U. (2010). Effects of modafinil and methylphenidate on visual attention capacity: a TVA-based study. Psychopharmacology, 210(3), 317-329.

- Mohamed, A. D. (2016). The effects of modafinil on convergent and divergent thinking of creativity: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 50(4), 252-267.

- Franke, A. G., Gränsmark, P., Agricola, A., Schühle, K., Rommel, T., Sebastian, A., … & Ruckes, C. (2017). Methylphenidate, modafinil, and caffeine for cognitive enhancement in chess: A double-blind, randomised controlled trial. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 27(3), 248-260.

About the Author

Sean is a consultant for clients in the pharmaceutical industry and is an associate lecturer at La Trobe University, where unfortunate undergrads are subject to his ramblings on chemistry and pharmacology.