The AIDS/HIV pandemic of 1981 took everyone by surprise. In the U.S., the FDA and pharmaceutical companies raced to test the effectiveness of drug candidates like AZT in clinical trials. Many patients turned to unproven, unregulated and illegal treatments like Peptide T, as portrayed in Dallas Buyers Club. But the film doesn’t do justice to the effectiveness of AZT, and the speed at which it was delivered to patients.

Peptide T is banned worldwide because there is insufficient clinical trial data to show that it is safe and effective against HIV. During the AIDS pandemic, people who wanted access to Peptide T and other non-FDA-approved drugs had to buy them through Buyers Clubs, often supplied by smugglers who were patients themselves.

Dallas Buyers Club vs Azidothymidine (AZT)

For those who haven’t watched the critically acclaimed 2013 film, Dallas Buyers Club tells the story of a patient diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and his fight against the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at the height of the mid-1980s pandemic. At the time, there was no official treatment available for AIDS, hence many patients sourced their drugs from so-called ‘Buyers Clubs’.

AZT – The First Drug Against HIV

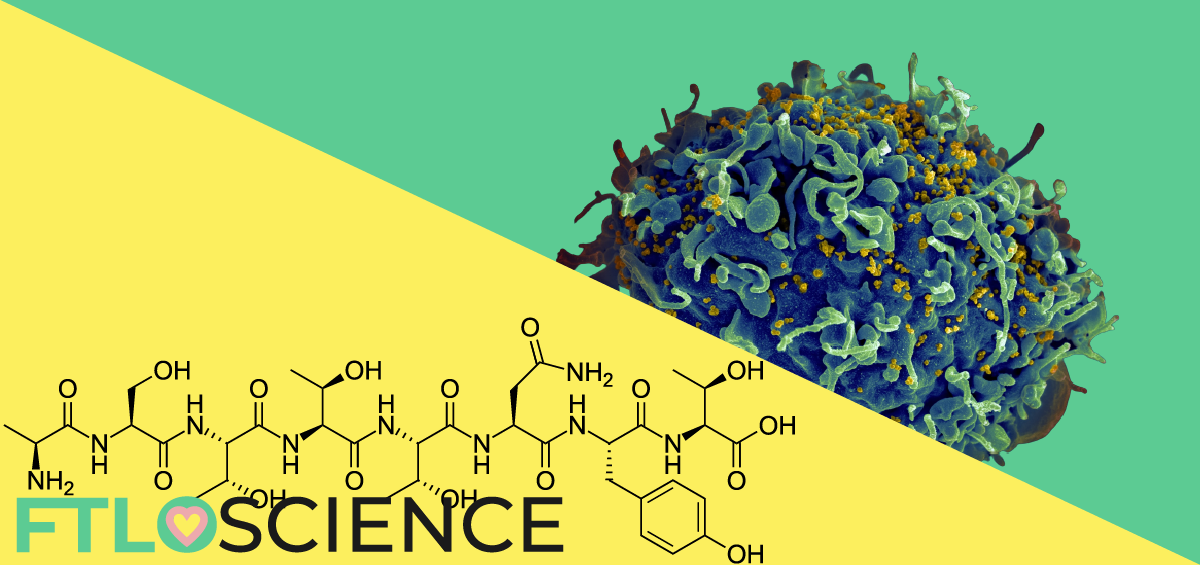

Having attributed AIDS to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), researchers began to look for suitable drug candidates that could stop or even slow the progression of the deadly virus. One promising early drug candidate was azidothymidine (AZT), a compound that had already been synthesized 20 years prior. AZT studies were conducted as early as 1963 for use against certain forms of cancer, but failed to meet endpoints and the medicinal chemistry program was shelved indefinitely.

In 1985, AZT became the first HIV drug that was available to patients via FDA-regulated clinical trials. But because these trials were placebo-controlled, half of the patients enrolled in these early studies weren’t receiving treatment at all. Instead of waiting for the drug to be approved and sold, many HIV patients began to source AZT from the black market instead.

Issues with AZT in Patients

Some patients also had bad experiences with AZT, regardless of whether they obtained it from clinical trials or more dubious sources. Clinical trials reported some serious side effects including bone marrow suppression, resulting in low blood counts1. Despite this, the overall outcomes of the trials were positive.

However, in Dallas Buyers Club, AZT is heavily condemned as an ‘expensive poison’. Many people believed the government and pharmaceutical industry were conspiring to sell AZT at high prices as the sole treatment for HIV/AIDS, while preventing access to other therapies deemed to be safer and more effective.

AZT’s performance in clinical trials, however, showed otherwise. The drug proved to be safe, and effective and increased the life expectancies of patients at all stages of the disease2. Such was its success that placebo-controlled trials were stopped early on, with all patients who were on the placebo given access to AZT instead. The 25 months it took for AZT to be approved by the FDA is one of the shortest periods of drug development in history.

Peptide T and Alternative Treatments

For AIDS sufferers, however, these 2 years in treatment limbo must have seemed an eternity. At the time, very little was known about the disease, and patients were wrongfully stigmatized due to the virus’ homosexual connotations. Who could fault them for pursuing alternative therapies?

Desperate for treatment that was both discreet and effective, secret groups of ‘Buyers Clubs’ were formed, where unapproved and often illegal drugs were smuggled into the U.S. and sold to patients. One popular treatment that is highlighted in Dallas Buyers Club was a compound called peptide T, administered via intravenous injection.

Peptide T was a drug candidate shown to prevent HIV infection in laboratory experiments, and indeed some individuals have even claimed that taking it prolonged their lives. As portrayed in Dallas Buyers Club, many patients swapped their AZT treatments for peptide T, despite it being an unapproved medicine.

To make matters worse, Peptide T never showed any convincing data on its effectiveness despite years of clinical trials. There is some evidence, however, that the drug can help with HIV-induced dementia and related cognitive impairments3. At the time of writing, the compound has yet to be approved for use anywhere in the world.

Addressing Flaws in Drug Development

The Dallas Buyers Club and the way people handled the HIV pandemic in its early years hold valuable lessons for regulatory agencies like the FDA. When a new disease sweeps through society, patients aren’t going to sit around waiting for an approved drug, which could take years before it becomes available on the market.

COVID-19 and Misinformation

The recent COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a prime example. During the period when COVID-19 vaccines were still in development, many communities and even doctors began their own ‘clinical trials’, providing unapproved drugs like hydroxychloroquine (originally for the treatment of malaria) off-label to patients of the disease.

In a setting eerily similar to that of Dallas Buyers Club, doctors would illegally write prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine to friends and family members as a treatment for COVID-19. After numerous clinical trials, however, there is still no indication that the drug counteracts the effects of, or prevents, coronavirus infection.

Despite the lack of evidence over a drug’s effectiveness or even safety, desperation drives some patients to use them off-label, essentially being ‘clinical trial’ volunteers in an uncontrolled, unregulated setting. But like the HIV-infected individuals of the ‘Buyers Clubs’, aren’t they simply victims of misinformation?

Changing the Clinical Trial Model

Part of the blame lies in the long, drawn-out and rigid clinical studies and the way they are handled. Even for novel diseases with no available treatment on the market, a patient’s entry into trials is subject to certain criteria and often long waiting times. Furthermore, many patients know that they might be receiving placebos, or sugar pills, with no therapeutic benefit.

While the traditional process of drug development is flawed, it is rigorous in examining the safety and efficacy of potential drugs. But it’s certainly not a one-size-fits-all model, with regulatory agencies and pharmaceutical companies slowly changing their approach to drug approvals and clinical trials.

Nowadays, placebos are rarely used in clinical trials for drugs that treat life-threatening conditions like cancer and HIV. For some of these drugs, phase 1 trials on healthy volunteers are scrapped altogether. There is also fast-track approval for novel therapies, all of which drastically reduce the time it takes for drugs to reach patients.

These are positive signs in the drug development landscape, perhaps saving people from turning to other ‘Peptide Ts’ in the future.

Reference

- Richmond, D. D., Fischl, M. A., & Grieco, M. H. (1987). The toxicity of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. New England Journal of Medicine, 317, 192-197.

- Fischl, M. A., Richman, D. D., Grieco, M. H., Gottlieb, M. S., Volberding, P. A., Laskin, O. L., … & Jackson, G. G. (1987). The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. New England Journal of Medicine, 317(4), 185-191.

- Heseltine, P. N., Goodkin, K., Atkinson, J. H., Vitiello, B., Rochon, J., Heaton, R. K., … & Feaster, D. (1998). Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of peptide T for HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Archives of Neurology, 55(1), 41-51.

About the Author

Sean is a consultant for clients in the pharmaceutical industry and is an associate lecturer at La Trobe University, where unfortunate undergrads are subject to his ramblings on chemistry and pharmacology.